King and Emperor

Reflections on two island monarchies

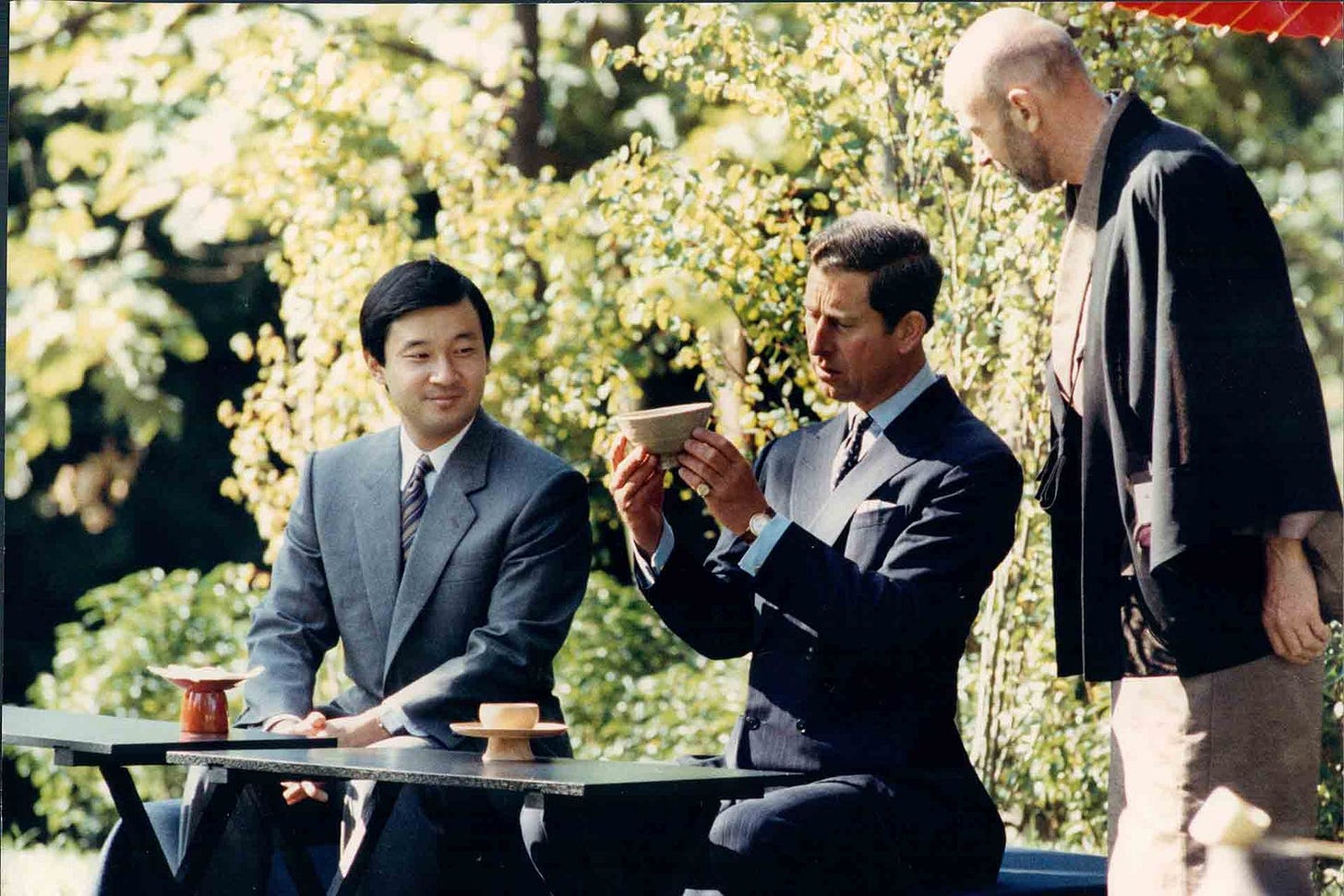

Over her long life, Her late Majesty forged friendships with leaders from nations all over. Emperor Naruhito of Japan was one such friend in attendance at the King’s coronation; while at Oxford he was hosted at Buckingham Palace and Balmoral, and on his own accession was invited back (though COVID scuppered it). But perhaps more interesting than this personal connection is the contrasting history of these two ancient monarchies, so similar in our own day.

“The United Kingdom” is a banal constitutional descriptor, but as a name “YooKay” increasingly beats out “Britain” and the older, incorrect “England”. The name is just one reason it is hard to imagine the British nation without its monarchy. But of course its predecessors have been conquered by foreign invaders, defeated and decapitated by radicals, and fled before a religiously charged Anglo-Dutch coup. Only with the firm establishment of the Parliamentary system and Hanoverian succession could the British monarchy enjoy its now unparalleled stability.

If the “United Kingdom” is over-literal then the “State of Japan” is not, a not-empire with an Emperor. But he can claim the oldest continuous monarchical legacy in the world, with a firmly historic record dating to the 6th century (and a legendary founding over a thousand years before that). Claiming descent from the Sun God, the early Japanese emperors were religious figures like the Pharaoh. To consolidate their temporal power the state was remodelled on the great Eastern civilisation, China - yet Japan soon fell into the recurring pattern of its history, rule of faction. First the great nobles, then the samurai usurped the throne’s prerogatives, but left it intact as symbol and legitimator for their own rule. The price of the imperial line’s longevity was its impotence.

With a system that permitted the keeping of imperial concubines and the ascession of their children, there was never the great risk faced by Christian houses, dynastic extinction. Nor was there Christian legalism and primogeniture, so younger sons often acceded, their sisters therefore only very rarely. And where a Chinese peasant could prove himself Heaven’s chosen by overthrowing a ruling dynasty, there was no precedent for an over-mighty samurai to proclaim himself emperor.

As a woman Victoria could not inherit Hanover, but as Queen of the United Kingdom at its apogee she could become Empress of India. The British royals were public figures: Prince Albert organised the Great Exhibition and founded South Kensington as we know it, while despite her place at the top of the world’s greatest empire, Victoria was sharply criticised when she withdrew from public life to mourn Albert.

In Kyōto the Japanese emperors remained secluded, restricted to the arts and ritual, their affairs micromanaged by agents of the shōgun - the samurai generalissimo. But the link to antiquity the imperial court represented remained an object of fascination. During the later Edo period, kokugaku nativist scholars looked to classical texts in search of a Japanese “soul” they thought had been polluted by the foreign teachings of Confucianism and Buddhism.

The Opium Wars, arrival of Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships”, and the unequal treaties that followed shocked the country; both China’s Son of Heaven and Japan’s “Barbarian Subduing Shōgun” (to give him his full title) had been humiliated by drug-running foreigners. Samurai radicalised by these outrages found inspiration in the work of the nativists, and turned to the imperial court as an alternative. Rallying behind slogans like fukko “Restore Antiquity” and sonnō jōi “Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians” the opposition coalesced, drew the Emperor back into politics, and finally overthrew the shōgun, proclaiming a Restoration.

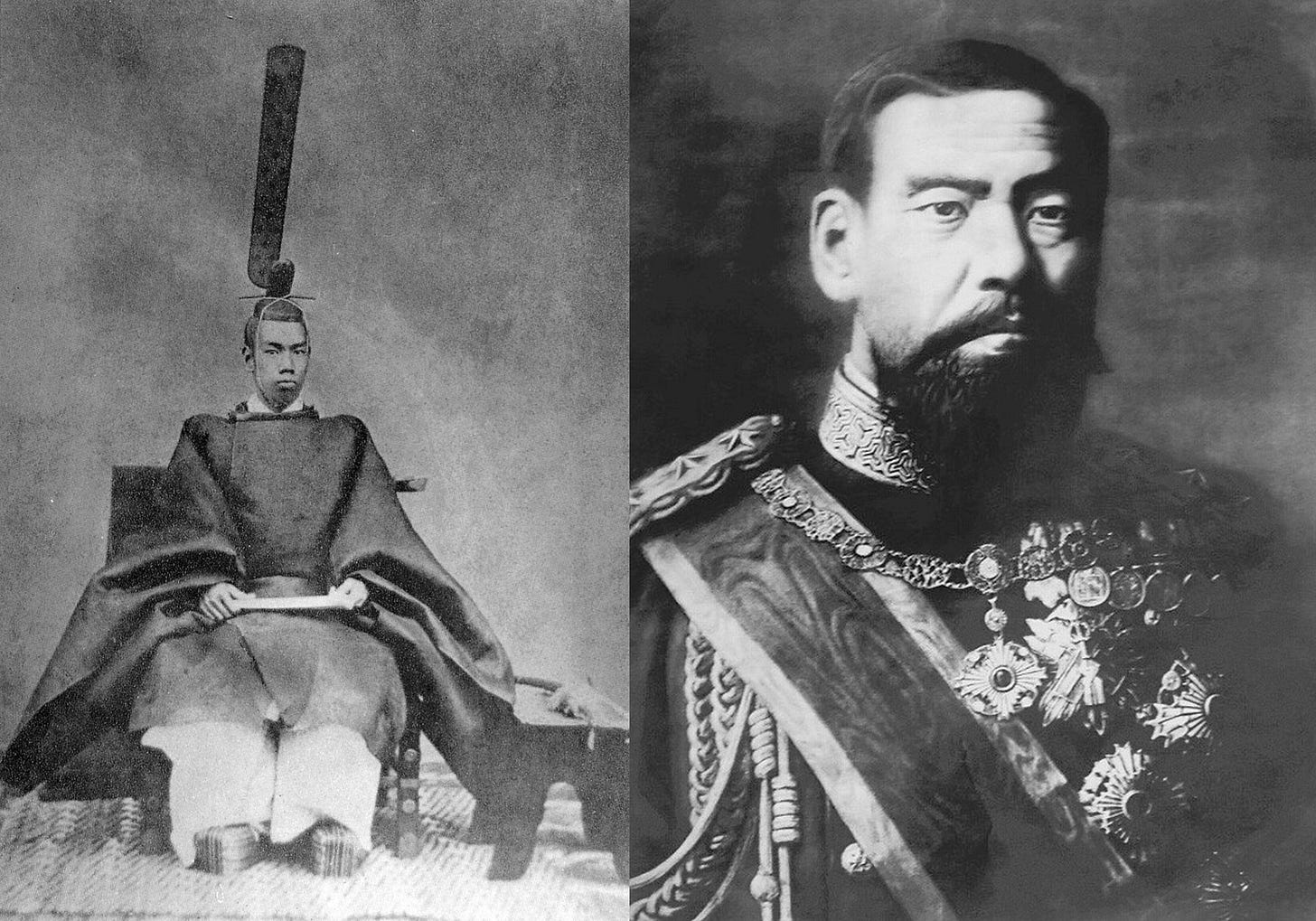

The young Emperor Meiji was central to the new order the Restorationists built though he did not rule as autocrat. The fragmentation of a centuries-old feudal order was dissolved by his aura of imperial charisma, as lords “returned” their lands to him. Itō Hirobumi, who wrote the Empire’s constitution and served as its first Prime Minister said: “In Japan, it is only the Imperial House that can become the axis of the state.” Rescripts emphasising imperial loyalty as the highest virtue were hung in every school and barracks. Strikingly given the calls of fukko and sonnō jōi that launched the Restoration War, Japan’s new leaders understood they would need to learn from the West to resist it. The new Imperial system of Cabinet, Diet, and Privy Council owed much to the British and Prussian examples they studied.

The emperor himself was westernised too: he swapped his traditional robes for a Western general’s uniform and sword, and grew a Victorian beard for good measure. Primogeniture succession was accepted and codified as in the West, while daughters were excluded to ensure the supposedly unbroken and divine paternal line survived. Conscious of how it had been weaponised by both regents and emperors of the past, Itō abolished the tradition of imperial abdication. Though the Meiji Emperor kept concubines his heirs did not, the women were pensioned off and another tradition was abandoned. Ironically, the modernised system that resulted is now more conservative than both its Western peers and its incumbent imperial family, and even threatens it with extinction.

The British monarchy was rocked by the Abdication Crisis, but survived and served honourably during the dark days of the Second World War. In Japan, Meiji’s son was namesake of the more liberal era of so-called “Taisho Democracy”. But the geopolitical and economic pressures of the interwar that followed Emperor Showa’s (aka Hirohito) accession in 1926 transformed it into a militarised “emperor system”, more total and radical than anything the Restoration leaders could have imagined. The cataclysmic war waged in his name only ended when the Emperor himself announced over radio - for the first time, and in court language few of his subjects fully understood - Japan’s unconditional surrender.

For the second time, Japan found itself at the mercy of a swaggering American. General MacArthur decided - as Itō had - that he needed the Emperor to build a new Japan, so cleared him of any war guilt by fiat and ended all talk of trials or abdication. This reprieve came at a price: renunciation of imperial divinity and sovereignty, and the demotion of all but the core imperial family. An unprecedented, famously unflattering photo of the Emperor, with MacArthur towering him, made the new state of affairs brutally clear.

Some Japanese gave into nihilism and despair in the immediate post-war, in the face of the collapse of their Emperor-centred world and the futility of their sacrifices. But on the whole MacArthur’s “mercy” and imperial continuity were popular, and the country quickly turned to the task of rebuilding. Remarkably, Hirohito transitioned from God and Supreme Warlord to a small-talking Sovereign, much like Her Late Majesty; the second time in less than a century that Japan’s oldest institution remodelled itself and became more Western, more British.

But the transition was not painless. Part of the post-war pruning was a new Household Law: any imperial woman who married a commoner forfeit her imperial status. With the abolition of their only suitable suitors in the imperial cadet branches, princesses leave rather than face a lonely and pointless imperial life (former Princess Mako being the latest in 2021). Consorts face impossible pressure to have sons as the imperial family’s duties fall on a dwindling number of shoulders. Even the Emperor Heisei (Akihito) had to ask for special dispensation to abdicate; and despite at least two decades of debate and only a single imperial heir under fifty, the government hasn’t intervened, scared to approach an issue so bound up with tradition. It is easy to forget the British crown adopted equal succession in 2013, so breezily it passed, in stark contrast to the Japanese deadlock.

The spontaneous and genuine mourning for the Queen was testament to the monarchy’s strength despite its many crises, and her leadership in navigating them. The predictions of pessimists and hopes of republicans seem far off; the people have warmed to King Charles, and already love his heirs. One suspects his fellow monarch the Emperor wished the foundations of his own monarchy were so secure.

Great piece, one might think given Japan's demographic situation the government would be doing everything in its power to encourage an vibrantly fecund extended Imperial family in the hopes of memeing larger families to the general population?

Fascinating. That the objections against female succession in contemporary Japan are based on "tradition" has always struck me as selective thinking, even special pleading, given the existence of at least half a dozen empresses regnant before the 19th century. Apparently, out of Japan's long monarchical history, which you have summarized so deftly, the "tradition" that contemporary conservatives value most is the most recent one, namely from the Meiji era, which, as you say, was heavily influenced by foreign models.